Not too far from the hustle and bustle of downtown Oslo, Norway is the Bydgøy Peninsula and its several museums, including a pair that focus on some of the most famous Norwegian explorers of the twentieth century. And while both museums tell tales of groundbreaking explorations, their stories have two very different morals.

The larger of the two is the Fram Museum, which bills itself as the best museum in Norway. The centerpiece of its exhibits are two of the actual vessels used to explore the ends of the Earth: Gjøa, the first ship to sail through the Northwest Passage that connects the Atlantic and Pacific in the Arctic (1903-1906), and the mighty Fram (“Freedom”), which was used by two Arctic expeditions (1893-1896 and 1898-1902) and the first ever expedition to the South Pole (1910-1912). Visitors can go inside the vessels, where crews spent years living on these ships very far from home (far from their homes and anyone else’s, for that matter). Supporting exhibits show the lives of intrepid explorers like Fridtjof Nansen, Roald Amundsen, and Otto Sverdrup, who made great contributions to multiple fields of science and sought to spread their appreciation of the native peoples they met and learned from.

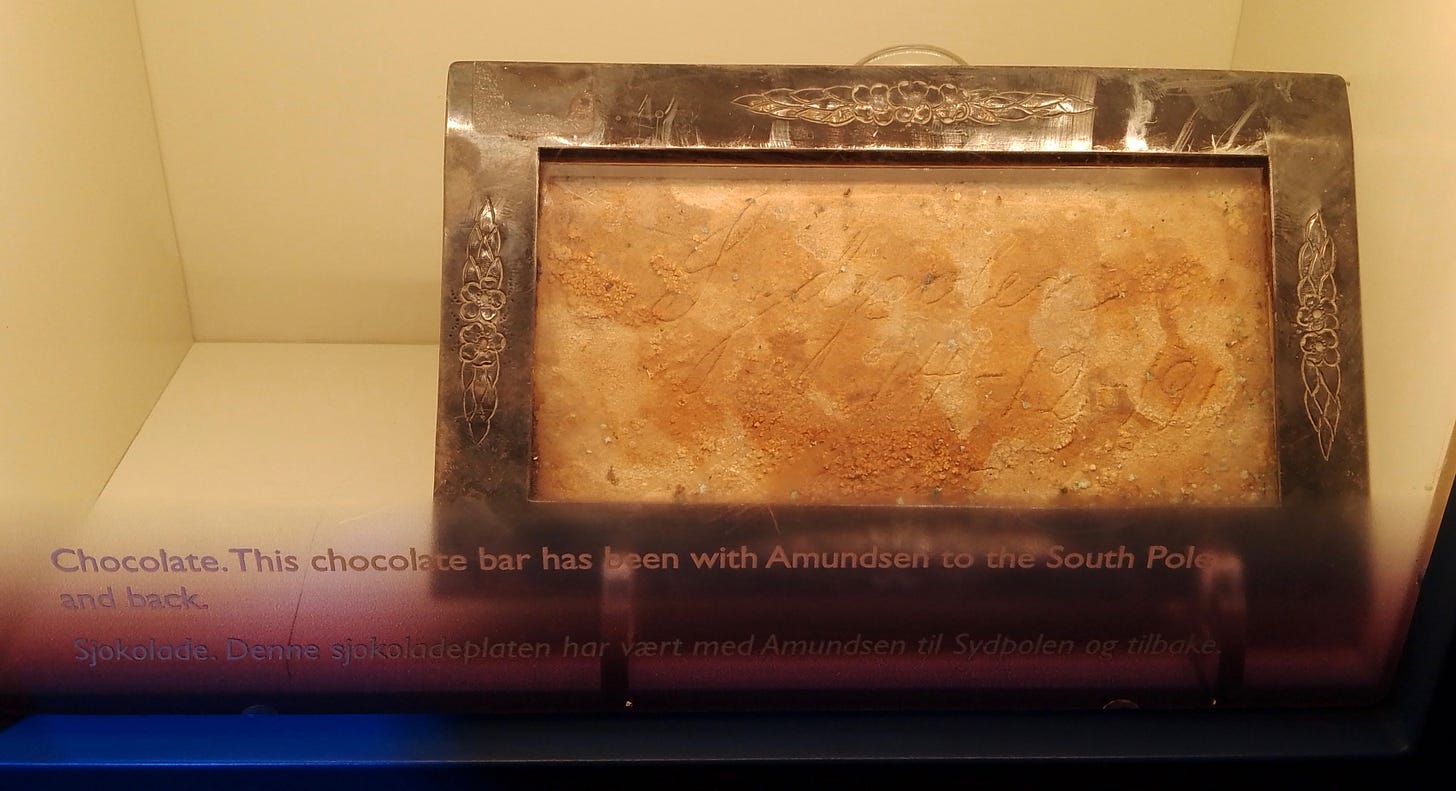

I always enjoy learning about the minutiae of life in museums, and the Fram Museum did a good job of showing what it was like living on a boat for years at a time surrounded by the same dozen men (and several dozen dogs). It turns out that successful expeditions often saw crewmen gain weight due to sufficient supplies and a lack of exercise. One expedition brought a tiny Christmas tree from Norway to go with their guaranteed white Christmas. Another published a newspaper, with the circulation limited to the men onboard. And two men who narrowly survived a polar bear attack photographed themselves reenacting the fight so they could more accurately tell the story when they got back.

The second museum is the Kon-Tiki Museum, which tells the story that you might know of a guy who built an ancient raft and sailed across an ocean in it. When Thor Heyerdahl was told it was impossible to sail on a balsa wood raft across the Pacific, he decided he’d prove people wrong and do it himself - and he succeeded. He’d go on to sail across the Atlantic on a reed boat and support efforts to foster world peace and protect the environment.

Like the Fram, the Kon-Tiki Museum also has two boats on display: the Kon-Tiki from Heyerdahl’s 1947 expedition and the Ra II from his successful 1970 journey across the Atlantic. (The Ra was lost near Bermuda due to a design flaw, but all crewmen survived and most returned to man the Ra II.)

The general thrust of both museums is the same: intrepid Norwegians “boldly go where no one has gone before” to further our knowledge of the world. But the best way to go about that differs between the two.

At the Fram Museum, careful preparation is key, and even expeditions led by experienced leaders can have fatal results. A wall of the museum shows a timeline of Roald Amundsen’s and Robert Scott’s two competing expeditions to the South Pole, side by side. The timeline shows Amundsen’s well-planned expedition proceeding relatively smoothly from base camp to the South Pole and back, while Scott’s expedition reached the South Pole only to find that Amundsen had beaten him by a month, and then on the way back slowly realized that they were doomed and then died alone in the frozen darkness. (There’s a reason the museum mainly focuses on the successful expeditions.)

But at the Kon-Tiki Museum, things are much more forgiving. If you were planning on funding an expedition to cross the Pacific, Thor Heyerdahl and his raft would not have been on your list of preferred choices. Heyerdahl was a weak swimmer, had never been a sailor and his raft had never been tested. But despite this, he and five others managed to sail more than 4,000 miles from Peru to Polynesia in the adventure of a lifetime (or for Heyerdahl, one of several adventures of a lifetime), and the film made about the adventure made him wealthy and able to continue his quests for knowledge and adventure.

Both morals have good points. If you’re doing something inherently dangerous, it pays to be prepared. And if you want to do something that people say can’t be done, you can gain a lot by doing it. It’s just where the two overlap that it gets tricky.

A Quote:

“The one who listens to his parents will live longer…and have a better life.”

- Netsilik proverb